On the 15th

of December, 2013, Nelson Mandela’s body was laid to rest in his home village

of Qunu. The massive, spontaneous outpouring of condolences and sympathy that

his death triggered was a clear manifestation of the respect Nelson Mandela

commanded around the world. The passing of a “giant,” as one magazine called

it, such as Mandela’s leaves behind in its wake the daunting task of evaluating

his legacies. In this article, I briefly reflect upon Mandela’s legacy. For all

the respect he commands, Mandela also has his detractors who question

the soundness of his legacy on two grounds. First, they question if Mandela

greatness has not been expounded beyond proportions by the lopsided reportage

of the media. Second, they ask if Mandela had done enough to protect the

interests of blacks in view of the huge economic inequalities seen in today’s South

Africa. Before facing these questions headlong, let’s step back, and begin by

looking into the character of the man in question – Nelson Mandela.

Born Free

The most

important feature of Mandela’s character was perhaps his being a free spirit.

In his autobiography, The Long Journey to Freedom[1], he

writes:

“I was not born with a hunger to be free. I was born free – free in every way that I could know. Free to run in the fields near my mother's hut, free to swim in the clear stream that ran through my village, free to roast mealies under the stars and ride the broad backs of slow-moving bulls. As long as I obeyed my father and abided by the customs of my tribe, I was not troubled by the laws of man or God.”

When it

downed on him that his freedom was curtailed by the apartheid regime, he stood

fearlessly to fight it. He neglected his career and his family, endangered his

life, and spent much of his youth and adulthood fighting the seemingly insurmountable

force of apartheid.

As much as

he was free and fearless, Mandela’s also possessed considerable

level-headedness. This character can be seen in his pragmatic approach to

politics, in his humane response to the grievances of apartheid, and the level

of self-assuredness he exhibited in all of those arduous years. No doubt his

personality evolved over time, and perhaps he owes his sagacity much to the 27-year

long incarceration he went through. In his autobiography, he describes how he

decided to maintain an unblemished spirit in the face of venomous adversity:

“I realized that they could take everything from me except my mind and my heart. They could not take those things. Those things I still had control over. And I decided not to give them away.”

Thus

Mandela managed to avoid becoming the monster he was fighting against, a trap

all too many freedom fighters fall into[2].

When he

spoke against apartheid, for example in the courtroom of his trial, he spoke in

a firm but measured tone. His arguments were never polarized – never to the

extent that would be expected from a person so unjustly accused, and was faced with a potential death penalty. He was charismatic, but never descended to

the folly of impressionistic or populist arguments. His logic was consistent, and, perhaps by design, easily accessible to his opponents. As a

politician this made him a trustworthy negotiator who could do business with

integrity. His ability to exude trust and integrity was indispensable in

assuaging the fears of the governing National Party which enabled it to arrive at a

negotiated solution with the African National Congress (ANC).

All said,

Mandela was a truly great persona that understood and fully believed in his

greatness, and was not afraid to show it to the world. He was the right man at

the right time. He was the grand spirit that applied itself to a great purpose,

with grit and consistency, until it was eventually met. Thus he saw through the

liberation of his people from an atrocious minority regime, and

became the first black president of his country. By no means does this mean

that he was perfect, and to that we will come in a short while.

The Unsung Heroes

|

A poster from the "Free Mandela" Movement showing the ANC helping Mandela's release. |

Although

Mandela is (perhaps rightly) presented as the face of the freedom struggle that

brought down apartheid, there are two other factors that played at least

equally important roles. The first is the leadership of the African Congress

Party, which was able to mobilize the masses and keep the spirit of the

struggle undimmed in a remarkably harsh environment. The second factor,

contradictory as it may seem, is the openness of the system of governance of

the apartheid regime. The predictable and law-based nature of the South Africa’s

administration was a crucial factor that contributed to a successful negotiated solution towards democracy. In the years

leading up to the 1994 election, there were several violent incidents involving

the semi-autonomous tribal states and extremist Afrikaner nationalist forces,

both of which wanted to either maintain the status quo or secede from the union and establish a separate

country. The active and constructive involvement of the Afrikaner National Party avoided the risk of a violent civil war that could have dealt a

catastrophic blow to the process of change. It is in recognition of this

contribution that the Nobel Peace Prize of 1993 was given not only to Mandela

but also to de Klerk who, although no other than an apartheid president, had

the cunning to see the “hand-writing on the wall” and acted in favor of change before it was too late.

Mandela the Saint?

Mandela,

however, is no Gandhi or Martin Luther King since he spearheaded sabotage and military action against apartheid. Although the ANC initially adopted non-violent struggle, it was forced to change its methods following the

brutal retaliation of the government that culminated in the Sharpeville

massacre of 1960. A year later, Mandela co-founded and became the head of the

underground military wing of the ANC.

In a

recorded speech, Mandela made the case for military action against the

apartheid regime:

“There are thousands of people who feel that it is useless and futile for us to continue talking peace and non-violence — against a government whose only reply is savage attacks on an unarmed and defenseless people. And I think the time has come for us to consider, in the light of our experiences at this day at home, whether the methods which we have applied so far are adequate.”

Mandela

argued that “The oppressor defines the nature of the struggle.” It is largely

for his involvement in bombings by this armed wing of the ANC, which led to several

deaths, that he was arrested in 1962 and sentenced to life in prison.

When, in 1985, the

then president P.W. Botha offered to release him if he rejected violence, Mandela spurned the offer, stating that "Only free men can

negotiate. A prisoner cannot enter into contracts." Still, Mandela

remained a champion of a negotiated solution during the long decades of his

incarceration. The final agreement that led up to a general election was

essentially engineered by Mandela in spite of initial opposition from his own

party.

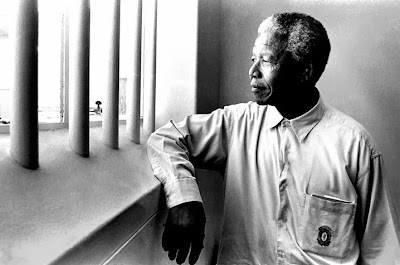

|

| A picture of Mandela visiting his prison cell in Robben Island where he spent 18 years, taken in 1994. |

Plastic Halo?

This brings

us to question of the extent to which Mandela’s crown of ‘halo’ is a fabricated

matter. If Mandela was not the only actor in the fight against apartheid, and

if he were not really the forgiving saint that some portray him to be, then

where does his current saintly picture come from? Although the issue is

unavoidably subjective, I would like to point out a couple of biases and

inconsistencies related to media coverage that contributed to this misrepresentation.

First of

all, the media tends to settle for presenting a rather stripped down, even superficial

version of reality that is targeted for the average audience. It is due to this

common denominator effect that much of the news coverage regarding Mandela

fails to fully present the complexity of the freedom struggle in South Africa. The

case for such shallow reporting is especially stronger when the setting is a

faraway country such as South Africa, so that nobody cares about the smaller

details.

Secondly, there

is the media’s tendency to repeat and magnify the sensual aspect of a story. Heaping

praise and glory on famous individuals is both cheaper and more sensual than discovering

new heroes, or going to the bottom of the story with all of its complexities. The

extraordinary life of Mandela makes him a natural target for a cult personality.

He is often presented as a statesman, a forgiving figurehead and a unifying

force of South Africa, while in fact in his earlier years he was a rather

militant freedom fighter. This narrative is also likely to gain currency since

it makes Mandela palatable to the tastes of the international audience who would otherwise find it hard to identify with a freedom fighter of a faraway

country. What transpired from his funeral, however, is that Mandela is loved and respected

among his own people largely for defying the brutal, minority regime of apartheid, and for sacrificing his life for fighting against it.

Mandela is more fittingly described as a practical and humane politician

with an indomitable spirit to win rather than as a saintly figure. Regardless of what the media says, Mandela

remains a great hero of his country and the world at large. Perhaps the most important

proof for this is the extent to which he was dearly missed upon his death by

his own people who knew him closely for decades[3].

|

| Mandela was sworn in as the first democratically elected president of South Africa in 1994. |

Liberty without Prosperity

Political

and economic freedom go hand in hand. It is fair to expect that South Africans

fought against apartheid not merely to be able to elect their own leaders, but

also to have full access to economic opportunities. Under Mandela’s presidency,

the government significantly expanded its welfare scheme by launching several

safety net programs that protected the economically underprivileged, and introduced affirmative action to encourage the participation of

blacks in the labor market. It also introduced a land reform to rebalance the

extremely skewed distribution of land[4]. Although

the economy benefited from these policies and rebounded rapidly, the majority

of blacks in South Africa still remain impoverished.

Critics point

out that the government could have taken more radical measures such as nationalizing

the mines and other sectors of the economy. Given the fall of the Berlin Wall

and the strong negotiation position of the National Party,

these radical moves were ruled out from the beginning. In any case, it is

difficult to argue that a mere redistribution of wealth could have redressed

the intractable economic challenges of South Africa. In fact, the ANC should be

praised for refraining from economic populism since poverty could be reduced

only by means of long term growth.

The

greatest strength of South Africa is not its wealth of gold and diamonds, nor

its relatively high level of income. What sets apart South Africa from other

African countries is that it was fortunate enough to inherit a set of political

and economic institutions that were designed to work for the settlers[5]. The

achievements of these institutions are already there to see in the country’s relatively

high quality of life, and in the successful power transfer from the minority

regime to an elected government in 1994. This makes South Africa part of a

select group of young countries such as USA, Canada, Australia, Singapore and

New Zealand that are unique for successfully transplanting the market friendly

and democratic institutions of Old Europe (Or to be more specific, those of Britain).

Because their inclusive nature, these institutions have the potential to

unleash economic prosperity by encouraging wealth creation via education and

entrepreneurship. The future of South Africa depends to a great extent on its ability to maintain and upgrade

these institutions so that they serve all citizens.

Of course

it will take many years before the broader public of South Africa could be

lifted up from poverty. The economic integration of the once-excluded blacks in

the US, for example, is far from complete five decades after the end of

segregation, highlighting the sluggishness of similar undertakings. It is perhaps fitting to

conclude by citing yet another remarkable statement of Mandela about the need for patience:

“The truth is that we are not yet free; we have merely achieved the freedom to be free, the right not to be oppressed. We have not taken the final step of our journey, but the first step on a longer and even more difficult road. For to be free is not merely to cast off one's chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others. The true test of our devotion to freedom is just beginning.”

[1] Here and elsewhere I am referring to his official autobiography “A

Long Walk to Freedom” that was published in 1995 by Little Brown & Co.

[2] The Irish poet W. B. Yeats wrote that “Too long a sacrifice can make a

stone of the heart,” which nonetheless is an assertion that does not apply for Mandela.

In an inspired article that intimates his relationship with Mandela, Bob Geldof

elucidates this point poetically: “The true miracle of Nelson Mandela is that

it did not [make his heart a stone]: 27 years of incarceration, he did not

break, and, most remarkably of all, his soul did not harden.”

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/nelson-mandela/10499624/Nelson-Mandela-Bob-Geldof-pays-tribute.html

[3] There is an important side

note here. The Western media has a significant clout that enables it to decide what

event is newsworthy, to frame it in its own terms, and even report it in a lopsided

manner. It is, for example, very likely that an event in South Africa gets more

media coverage than a comparable event in another country due to South Africa’s

tight relationship with England. Here is an informative example of how the

western media adjudges what is newsworthy. Everyone knows Colonel Idi Amin

Dada, the brutal dictator of Uganda in the years 1971 - 1979. In those years,

the western media was awash with news reports from that impoverished country,

although, the content of the coverage grew dimmer through time and eventually turned

against the dictator. The interest in this dictator was so significant that the

famous film about him that was released after his death, “Last King of Scotland,”

was a box office success. In these same years, close by Ethiopia was ruled by

another dictator, Colonel Mengistu Hailemariam, who oversaw a disastrous reign

of terror and civil war in the country. Under both dictators, it is estimated

that hundreds of thousands people perished. Nonetheless, there was a much less

news coverage from Ethiopia than Uganda. Even today, googling the names of the

two dictators reveals that Idi Amin Dada gets almost 100,000 more search hits

than Mengistu Haile Mariam, although the later was a dictator for twice as many

years and over a much larger country. How do we explain this significant

difference of interest between the two dictators? The answer lies in the strong

relationship of Uganda with Britain, which was its past colonial master, as a

result of which Uganda is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. The British also

had a vested interest in maintaining peace in Uganda because of the presence of

a large Indian settler community which was one of the legacies of their colonial

rule of the country. When their relationship with Idi Amin Dada finally

collapsed, he displaced thousands of Indians who eventually came to England and

had to be provided for. The point here is that, not surprisingly, the Western

media sees things through a western angle, leading to a differential treatment

of affairs that are otherwise similar.

[4] The 1913 land reform had shrunken the proportion of land owned by

black South Africans to a mere 7%, although whites constitute only 9% of the

population in present day South Africa.

[5] In most other African countries, colonizers built exploitative

institutions that facilitated the extraction of natural resources rather than

boosting economic growth. These institutions were then passed onto the newly

independent African nations at the end of colonialization. For institutional difference

between settler and non-settler coloines, see: Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and

James A. Robinson, 2001. "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development:

An Empirical Investigation," American Economic Review, vol. 91(5), pages

1369-1401.